Reason #7 / Reuben Schoots / Watchmaker

The Mechanic of Time…

Scroll ↓

Reuben Schoots / Watchmaker

Reuben Schoots is an independent Australian watchmaker. As a 'self-taught' first-generation craftsman, he has embarked on a feat only accomplished by a handful of people in the world.

Known as 'The Daniels Method', Reuben is making a Tourbillon pocket watch from George Daniels' book Watch Making, using only hand tools and manual machines. After four years, he has just one more mechanical component left to make. In the meantime, Reuben is a few months away from finishing his First Series release wristwatch. Limited to six watches, they were all pre-sold within 40 minutes without an official release.

In 2015, After contracting a life-threatening illness during his travels to South America, Reuben was forced to re-invent his life as he knew it. A journey into the world of Horology ensued. Remarkably, Reuben has only 4.5 years of watchmaking experience; it usually takes decades, and he is still only 29 years of age...

Reuben reached out to me via Instagram in late May 2022, hoping to have his First Series wristwatches documented and photographed by me. With a personal interest in watches, I've had similar enquiries from others in the past; but Reuben was the first to introduce himself as an actual 'watchmaker'.

Curiously, I Googled his name. The next minute, I was on the phone with Reuben; then, shortly after, I was on a plane to Canberra to meet the man...

'That watch represents so much. It represents the moment my life took purpose and meaning, and I am grateful for what it has taught me...'

- Reuben Schoots

27th July 2022.

I can't remember the last time I was on a plane...

Once on board, I feel claustrophobic, like a masked sardine in a tin can, and I can't wait to get to my destination.

Relieved after landing, I hail an Uber to Reuben's home, located just South of Canberra.

On arrival, I take my mask off, breathe in the crisp morning air, and take in the picturesque view of the Bullen Range hills soaring above the suburban houses.

As I approach his home workshop, I catch Reuben's attention through the glass doors. Wearing a sleeveless black puffer jacket, he's tall, youthful, and has a presence; I immediately notice his piercing eyes.

He greets me warmly and immediately gives me the tour.

First, he shows me through his 'clean room'. It's a clinical light-filled white room with longitudinal benches on each side. A desk sits at the far end of the room, under a window, with a view of his backyard. He says he and his wife Cielo were recently married 'out there'.

Neatly arranged on the side bench are numerous machines. Reuben explains that he has made or modified many of them; I am surprised to learn that Reuben also makes his own tools.

Next, he takes me to the adjoining 'dirty room'. It's a typical 1980s Aussie drive-through shed with steel roller doors at each end. There is a large lathe on one side and a *CNC machine on the other. He is keen to tell me that he recently built the machine with his mentor, Lindsay.

* A Computer Numerical Control (CNC) router is a computer-controlled cutting machine that typically mounts a hand-held router as a spindle, used for cutting various materials such as metal.

For the first hour or so, I am engrossed with Reuben and hanging on to his every word. Realising that I haven't taken a single photograph, I tell him to continue with what he had planned for the day.

His goal today, he tells me, is to finish (polish) some watch components for his First Release wristwatch and make some 'minute hands' for his watch on the CNC machine.

He begins at his computer screen and starts programming the CNC machine; then, he heads into the 'dirty room'. As the machine starts up, he bends over and leans close to examine the tool as it works away at the sheet metal. I notice his eyes again. With a look of intense concentration and a distinct 'glint', his eyes look alive.

Deep concentration becomes the theme of the day.

Next, He heads to his desk and sits beside a microscope. He explains that watchmakers traditionally use a monocle, but he prefers modern technology because it allows him a more macro view. He says it's also better for his posture - not having to bend down low to his desk.

As he buries his head into the microscope, I catch the glint in his eyes again.

Using a pair of tweezers, he picks up a tiny watch component that I can barely distinguish with my naked eyes. He explains that the element is a 'ratchet pawl', a part of the 'click works'.

He goes on to explain.

'The piece engages with the winding wheel and is responsible for not allowing the main spring to unwind when the watch is wound up. Think of it as the knot in a blown-up balloon stopping the air from getting out', says Reuben.

I ask what he is doing with it.

Reuben: 'I am trying to achieve a level of finishing that is as close to perfect as possible; graining the top surface of the hardened steel with a 20-micron paper to give it a nice brush finish and applying a chamfer beveling around the edges of 45 degrees with a high polish. I am putting a lot of effort into this component because it's the part the owner can see moving when they wind the watch'.

Reuben alternated between his desk and the CNC for what seemed like hours, and he kept working on the same components at his desk.

He says the process is prolonged and requires immense patience because you can easily ruin a component during the finishing process. Ironically, he admits during our Zoom interview a week later that he had to remake those 'ratchet pawls'...

Reuben continues as the day passes, but I notice he begins to waver at around 4.30pm. He says he knows his physical and mental limits these days. At that point, he mentions that he loves to clean and heads into the 'dirty room' to grab the vacuum cleaner.

After the clean, I asked Reuben if he could show me his yet-to-be-complete George Daniels Tourbillon pocket watch.

He says, 'of course', opens a drawer and pulls out a ubiquitous plastic box.

He removes multiple components from the parts box onto his desk and begins to piece them together; It's like watching a surgeon at work.

As the late afternoon light bathes his desk and face, he continues, and I notice his demeanour change. Whilst his concentration was still there, it was less intense, and his facial expression was more relaxed, a hint of pride, perhaps? I feel like I am witnessing a tender moment...

Back in Melbourne, over our Zoom interview, I ask Reuben about 'that moment'.

Reuben: 'I hadn't touched that watch for 12 months, so I felt a lot of emotions at that moment. I felt a bit sorry for myself...but not in a bad way. I remember everything I put myself through to make it; each component has its own story...'

'I also looked at it in a caring way. It's almost alive; it's a thing...'

'That watch represents so much. It represents the moment my life took purpose and meaning, and I am grateful for what it has taught me. I'm a much more levelled human being now because of that experience'.

'That experience' happened in 2015...

At 22, Reuben travelled to South America for a holiday. While there, he contracted a tropical virus and a parasite and became quite unwell. Reuben was constantly fatigued, lost weight, and had intense rebound depression due to the illness.

Reuben: 'When I got sick, all the pillars that made up my personality and how I identified with myself were gone. I was put off work; my social life was stripped away, and a large part of my identity was gone. I was no longer a Man; stripped back to my core, I felt like a vulnerable boy...'

'It took me over 2 years to recover, but it was a valuable experience for me in the sense that it cleaned my plate, and I was able to start (life) again'.

During that time, he revived his love for mechanical things...

Reuben: 'I first became interested in mechanical things when I was a young boy. I was fortunate enough to be my father's apprentice at 8 years old when he restored a 1961 Triumph TR4 (a little British racing car) ...'

'What I took out of that experience was the relationship of mechanical parts working together. How human hands can then intervene, take something broken, and restore it back to its original glory'.

During his recovery, Reuben stumbled onto an alternative mechanical pursuit - the art of 'watchmaking'; and he became obsessed with clocks and watches.

Reuben: 'I began looking inside mechanical watches and took apart a clock in my family home, and questions started to arise. How are these things serviced? Who services them, and how are these things made?'

Having never heard of 'watchmaking' as a profession, he spent hours on YouTube watching videos. Intrigued, he purchased a Chinese mechanical watch with a clone of a Swiss movement to try his hand at 'watchmaking'.

Reuben: 'I ordered some screwdrivers and some tweezers, and when the watch arrived, I took it apart and put it back together again. From my understanding (at that time), that was watchmaking...'

It's interesting to note that most modern watchmakers only repair watches since most watches are now factory-made. However, initially, they were master craftsmen who built them, including all their parts, often by hand. Reuben was more interested in exploring the latter.

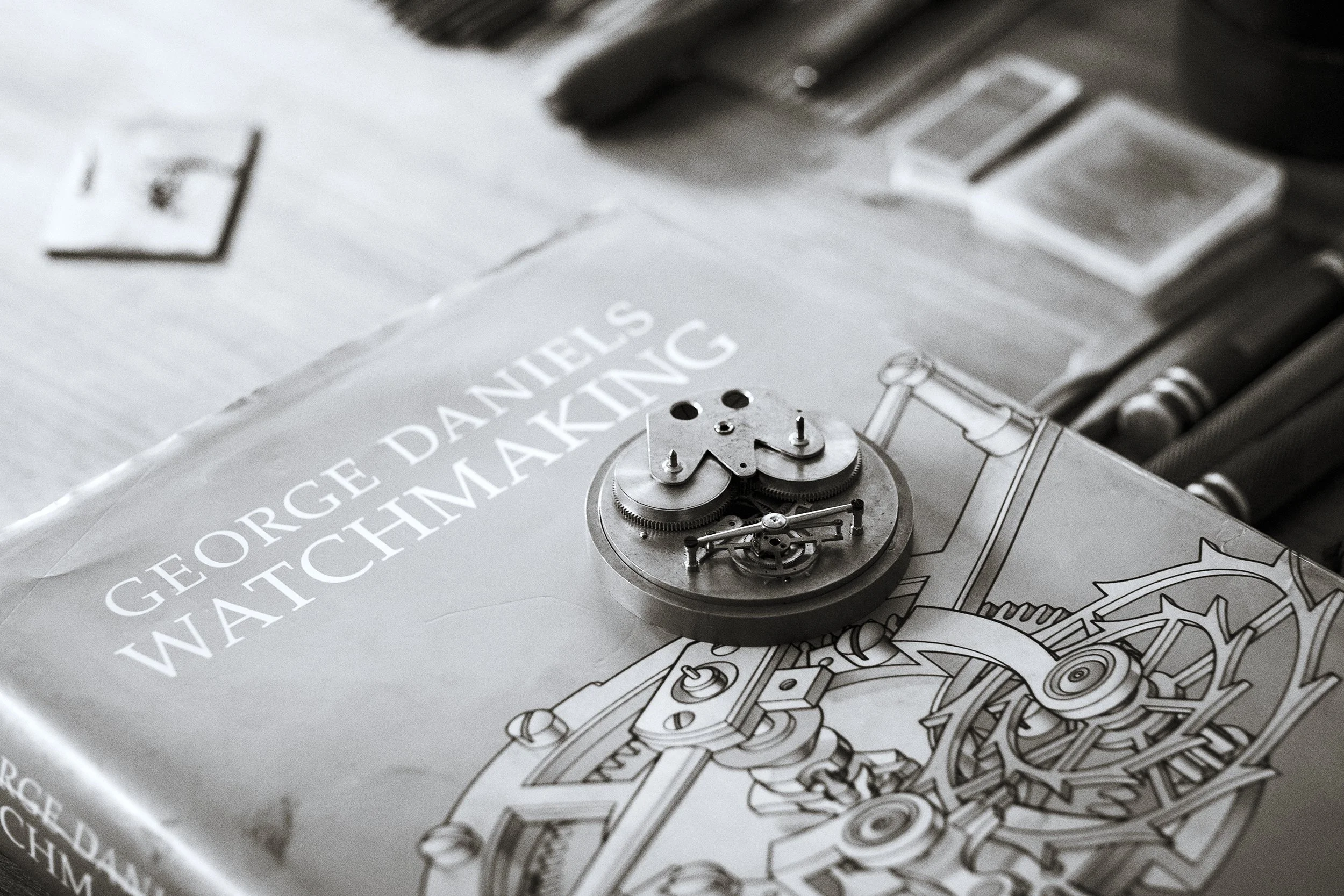

Reuben: 'On first search basis, I essentially discovered nobody. Then I came across the book Watch Making by George Daniels and "The Daniels Method" as it is called: one person making a watch with their hands. This intrigued me hugely; it became an obsession, trying to figure out how someone could do this'.

'I ordered the book and read it in a fortnight. It was incredibly strenuous; I was still quite fatigued from my illness. I read it again and then wrote down all the tools I would need to start, and on New Year's Eve 2017/18, I decided then and there that I would attempt to make his Double Barrel Tourbillon pocket watch...'

The watch in question is a precision chronometer and is a distillation of the best horological innovations throughout history. Inside is a complication called a Tourbillon (whirlwind or carousel in French). A timepiece with a Tourbillon is highly sought after by collectors and is a very complex and beautiful mechanism. It rotates the escapement (the part of the watch movement responsible for 'keeping time') through 360 degrees in a given interval. This equals out and eliminates gravity's negative effects on timekeeping.

I ask Reuben to describe George Daniels and his significance.

Reuben: 'As an English Horologist, George Daniels (1926-2011) revived the idea that one watchmaker could make an entire watch by hand. To the best of my knowledge, Daniels was the first person to ever do that for the better part of the century. He accumulated all the essential machinery and the knowledge to do so. There are 32 individual trades or disciplines that make up watchmaking, and Daniels was able to master all of them. He has inspired a whole new generation of watchmakers like me'.

To begin his mammoth challenge, Reuben bought a small watchmaker's lathe and a basic set of hand tools to start making components for the watch. When the lathe arrived, he didn't know how it worked; it also had no power. So, he took an old sewing machine apart, removed its motor, and adapted it to work with the lathe.

'It wasn't ideal, but I got it working', Reuben says.

'I then set out about making the first two components of the watch, of which there are around 300. I initially started on a screw and the mainspring barrel (the first wheel in the gear train and where the watch's spring lives). The screw was fine, but the barrel wasn't functional because I had an issue with the teeth - their formation wasn't perfect. I didn't understand the fundamental principles of precision required. The first one took a whole month to make, a part that usually takes around 8 hours of work'.

Reuben found it frustrating for a man of his generation that there was not a lot of watchmaking content out there. He was so used to being able to research and discover things online.

Disconsolate, Reuben went to a local Clock and Watch Exhibition, searching for answers. There, he met Lindsay Drabsch, an engineer in his 80s nicknamed 'the man who can make anything'.

Reuben: 'He had all these hand tools and jigs that solved all my problems; it was mind-blowing; he demonstrated the exact issue I was trying to solve. Since that day, I have apprenticed him and over a year spent one day a week making machines and tools with him'.

Lindsay also introduced Reuben to Roger Little: a local watchmaker in Canberra.

Reuben: 'He has the Ferrari of watchmaking tools and machinery, and he is a real tools enthusiast with over 50 years of experience in watchmaking. He became my second mentor, demonstrating hand skills and how to use the machinery'.

I ask Reuben if 'tool making' is also his new passion.

With a huge grin, he responds: 'Absolutely! I love it so much, and it is the best...'

'I've made 100s of tools and have utilised at least two-thirds of them to make the George Daniels watch. While thorough in its step-by-step instructions, his book doesn't detail the exact tools required. It's up to the individual watchmaker to use whatever tools will solve their problems. All my tools are unique to me, and often you need to make a tool to create another.'

While George Daniels stuck to hand machines and tools, Reuben has embraced modern technology moving forward for his wristwatches. Whilst CNC machines suitable for watchmaking exist, they cost hundreds of thousands of dollars which Reuben couldn't afford. He is particularly proud of his bespoke CNC machine, which he built with Lindsay.

Reuben: 'As a precision engineer, Lindsay was interested in watchmaking, and while the traditional watchmakers stuck to handworks only, he convinced me that historically, watchmakers were the ones pushing the envelope with technology. He thought I would be a true watchmaker if I embraced new technology rather than ignore it. So, we set out to make one...'

The experienced engineer was an early adopter of CNC, and Lindsy built his first one in the late 1980s, but Reuben required a much higher precision machine more suited for making tiny watch parts.

Reuben: 'Lindsay advised that if I could work out what hardware we needed to use, he would help me put one together. We made the physical machine without all the electronics, so it had no power, computer chip or motor. It was up to me to do the rest. Over the next month, I made all the plugs and the cabling, put the motor on, and did all the required programming. It was a huge learning curve'.

Unfortunately, after initial testing, Reuben discovered that it had an error of 12 microns; he needed it to be 5 microns or less. So, they made another one...successfully.

He then had to learn 3D modelling in CAM (Computer Aided Manufacturing), which he says was a whole other journey. The technology now enables Reuben a whole new level of creativity.

With his knowledge and passion now deep into modern tech, I am curious about where he ended up with the George Daniels Tourbillon, which he committed almost 3 years of his life.

Reuben: 'I have only one more mechanical component to make. But that watch has taken a sideline for the moment because it doesn't offer me an income. Instead, I am now concentrating on making my First Series. I realised that creating that watch was many things, but it was primarily the makings of the workshop. It's another tool in my life - a journey'.

'My dream from the beginning was to make wristwatches of my own design. The George Daniels Watch was an exercise in hand skills, and I will not be making my wristwatches in that style. As you know, I am embracing modern technology with CAM and CNC, which are, in fact, two more disciplines beyond the traditional 32 watchmakers' trades'.

Speaking of his own wristwatch design, Reuben began prototyping his First Series in August 2021, when Canberra went into its first pandemic-enforced Lockdown.

Reuben: 'I was struggling to stay motivated with clock repairs which I was doing for income at the time. My customers weren't allowed to visit (due to the Lockdown), so I took the opportunity to start work on my first wristwatch design'.

'The prototype took 3 months. It was an amazing experience; I was back into watchmaking, and it was so awesome...'

At the time of my visit, he had completed the machining and making of just over 150 individual components from raw materials, with finishing (polishing) still to come. He estimates the six watches will be complete by the end of this year.

Over the next few years, he plans to make up to 98% of the watch components himself, which will mean making the wheel train and even the escapement as he did for his Daniels Pocket Watch.

'That's what interests me, and not because it's good business', says Reuben.

I ask Reuben how he copes with the intensity of mental and physical concentration required for watchmaking.

Reuben: 'In the early days, sometimes my evenings were terrible. You'd work as hard as you could all week and lose a part or accidentally break one. So, I developed some coping mechanisms and started going to the sauna. It helped me with time out, just focusing on your body as a physical challenge. I also began swimming laps underwater. It's peaceful underwater with no distractions - nothing else matters except breathing. I also stretch for over an hour daily in my backyard; it removes all my tension'.

So, what does the future hold for Reuben?

Reuben: 'The challenge never ends, and I will constantly aim for perfection, mechanically and aesthetically. I try not to look at what other people are doing because it clouds my mind. I am trying to finish my watches without the influence of what they should be. External expectations corrupt me a lot constantly. There's a great phrase in George Daniels' book...'

'Nobody can show you how to make a watch...'

'Cielo, my wife keeps reminding me - if you do your best work, nothing can hurt you because it's your best'.

'I want to keep the watchmaking tradition alive and put Australia on the map. My long-term goal is to keep producing Australian handmade watches. Unashamedly, I am a self-taught Australian watchmaker; I am not trying to be a second-generation Swiss...'